Contents

I. Introduction

II. Geography

III. Climate

IV. Culture

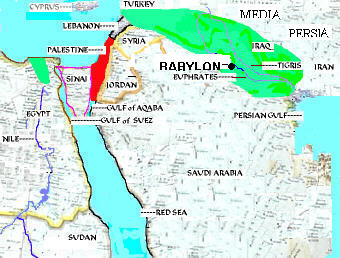

Figure 1 The Fertile Crescent

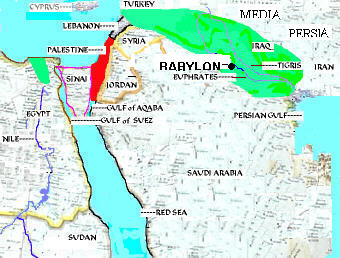

Figure 2 First-Century AD Palestine

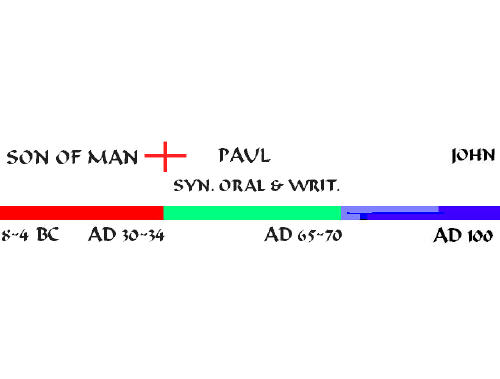

Figure 3 Gospel Timeline

Table 1 The Clash of Two Value Systems

Table 2 Intertestamental Chronology

Our God in the person of our Savior Jesus Christ entered human history in a region of the world known as the Holy Land, or Palestine. Modern Palestine is approximately coincident with modern Israel and parts of Jordan. It is expedient for the believer to study the character of this region in order to better understand and appreciate the New Testament witness to our Savior's life. This summary-study will investigate the geographical, climatic, cultural, and intertestamental character of Palestine, with an eye to its place in and impact on the events of the New Testament. [1]

The word Palestine is a derivative of Philistia ("Palestine"), the name given by Greek writers to the land of the Philistines, itself an ancient (c. 1200 BC) five-city confederacy comprised of Gaza, Ascalon, Ashdod, Gath, and Ekron ("Philistines"). "The name Palestine has long been in popular use as a general term to denote a traditional region, but this usage does not imply precise boundaries" ("Palestine").

The major civilizations of the ancient world developed in and adjacent to the Fertile Crescent. This fertile expanse of land arches across Palestine and the Syrian Desert from the Nile Valley in the west to the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and their respective bottoms land north of the Persian Gulf in the east. Palestine lies in a commercially and militarily strategic location roughly near the middle of the crescent, land-bridging three continents—Eurasia to the north and northwest and Africa to the south (Fig. 1). Naturally the major trade routes of old passed through Palestine—Palestine’s value as a commercial highway together with its value as an intercontinental staging area and conduit for military operations suggests that the major ancient empires of the area coveted Palestine. Indeed, the Egyptians, Hittites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Media-Persians, Greeks, and the Romans all controlled Palestine (and all or most of the Fertile Crescent) in their heyday. Religious convictions notwithstanding, Palestine was (and still is) a hotbed of conflict in no small part due to its location.

Palestine has two distinct natural boundaries that generally flank its western and eastern borders. The Mediterranean Sea bounds the region on the west, and the Arabian Desert does so on the east (the Arabian Desert covers most of the Arabian Peninsula and lies south of the Syrian Desert and southeast of Jordan). Palestine is a relatively small and narrow strip of land; its average width is 100 kilometers, while its length is approximately 240 kilometers (Palestine/modern Israel would fit into the upper one-half of the American state of Florida with plenty of room to spare[2]). Significantly, there are no natural harbors along its Mediterranean shoreline.

It is advantageous for us to study the general north-south lay of the land transversely[3] Let us therefore start at the shoreline of the Mediterranean Sea in the west and cut across Palestine to the edge of the desert in the east. If we approach our study in this manner we will encounter six distinctive topographies as we traverse Palestine.

We first encounter the Mediterranean Coastal Plain, which is comprised of contiguous lowlands. This plain runs the length of Palestine, generally parallel to the shoreline of the Mediterranean Sea. It is featureless, flat, sandy land that was used as a highway by the ancient trade merchants. One of the major trade routes of old, the Via Maris (=”Way of the Sea), which ran from Egypt up into the Fertile Crescent, made use of this plain. ("Sharon, Plain"). The Mediterranean Coastal Plain’s most northerly lowland, the Plain of 'Akko, which is on the Lebanon border, extends approximately 32 kilometers southward to the Carmel Promontory in Israel. The Coastal Plain’s breadth varies from 8-14 kilometers in the north, to as little as 180 meters in the south in the vicinity of the Carmel Promontory (also called Cape Carmel). Further south the Coastal Plain reopens to a width of approximately 13 kilometers as it extends into the Plain of Sharon, and to as much as 40 kilometers further south yet, giving it somewhat of an elongated hourglass shape. It can easily be appreciated that given an area based on an average 100 kilometer width for Palestine proper, the Coastal Plain in comparison (much smaller width on average, roughly the same length) makes up only a fraction of that overall area. Its value as thoroughfare, nonetheless, oftentimes shook the entire region, and beyond, as empire after empire endeavored to possess and maintain it, thereby shaping world history.

Upon leaving the general area of the Coastal Plain moving eastward and inland we encounter the second significant geographic feature of Palestine, namely the rather triangular shaped desolate wilderness of the Negev Desert region in the south, positioned with its apex touching the Gulf of Aqaba, the northwest corner of its base touching the Sinai Peninsula, and the northeast corner of its base touching the Dead Sea. The base of this wilderness lies on average at approximately 31 degrees latitude.

Just north of the Negev, slightly off the centerline of its triangular shape (to either side), begins the generally north-south trending Hills of Judea region, which marks the beginning of the Central Highlands, our third significant geographic feature. The Central Highlands was oft-used as a basing area by the Maccabees in their war with the Seleucids, discussed below. This rugged, and very difficult to negotiate hill country shunts the Plain of Sharon lying on its western side, and runs north into the Carmel Range. The Carmel Range is a northwest-southeast trending mountain range punctuated by Mount Carmel at 597 meters above sea level (Mount Carmel is where the Lord's servant Elijah shamed the prophets of Baal—1 kgs. 18 ). The Carmel Range naturally divides the Plain of Esdraelon, lying to its northeast, from the Plain of Sharon, lying to its southwest. The Plain of Esdraelon contains the Valley of Jezreel on its southern edge (Josh. 17:16, Judg. 6:33, Hos. 1:5, “Jezreel Valley”); this valley is literally a breach in the Central Highlands, and is the only natural means of entrance into the heartland of Palestine for an enemy approaching from the west. King Solomon stationed troops at Megiddo, a city on a mountaintop overlooking this valley, to defend Israelite Palestine from invaders from the west (1 Kgs. 9:15). The combination of a naturally harborless shoreline in the west, rugged Central Highlands further inland, and desert in the east, meant that Palestine was most vulnerable to attack from the north and the south. Indeed, in 722 BC when the Assyrians conquered the northern kingdom of Israel, and again in 587 BC when the Babylonians conquered the southern kingdom of Judah, invasion came from the north. The main threat from the south came from Egypt—but Egypt largely played the role of suzerain to Israel and so we find that front protected by the main threat itself. This Egyptian protection was both willful, and “by association”—the former for Egyptian economic and political expediency, the latter for the would-be invader’s expediency, for to trifle with a subject was to trifle with the suzerain, and oftentimes the nations of the Middle East were no match for mighty Egypt. These past lines are appropriate even up to the period just prior to the Babylonian captivity, for when Assyria collapsed in the seventh-century BC, Egypt, as also Babylon—which would ultimately fill the power vacuum—was strong enough to at least make a play for control of Palestine. Of course in the days of Jesus Palestine was under Roman control and the entire threat picture here discussed was completely different.

Our fourth topography borders the Plain of Esdraelon to the northeast: Lake Galilee in Galilee as also the beautiful Plain of Gennesaret to the northwest of Lake Galilee (“The Paradise of Galilee”) lie in a relatively cool and moist and well-wooded region; this region provides a fair contrast to the rest of Palestine. The Galilee region is much more fruitful than most of the rest of Palestine. This is not because it receives appreciably more rainfall, but because the westerly winds bring to Galilee consistent year-round moisture from the Lebanons (Smith 418ff).

Continuing our journey eastward the fifth geographic feature beyond the Central Highlands and Galilee that we encounter is the seismically active Jordan Valley, which is part of the Great Rift Valley, one of the most far-reaching rift systems on the earth (6400 kilometers). The Great Rift Valley houses the Jordan River and the Dead Sea ("East African Rift System" [this article alludes to Evolution, which we thoroughly disavow; its value lies in its geographical and geological scholarship alone in our opinion]). The Jordan River, the lowest river on earth ("Jordan River"), originates in Syria at the foot of Mount Hermon, itself the highest point on the east coast of the Mediterranean Sea. It then flows south into and out of Lake Galilee; from there, it continues southward and empties into the Dead Sea, which is the lowest spot on earth (approximately 400 meters below sea level).

Particularly the northern end of the valley possesses fertile soils, abundant water, and maintains a year-round agricultural climate. “Jericho, we have seen, was a very flourishing region, especially in the hands of the Romans who knew how to irrigate. There seems to have been a continuous forest of palms all the way hence to Phasaelis. Further up the valley at Kurawa, there are fertile fields, and the richness of the country round Bethshan is evident. The whole of this side of the valley was famed, throughout the ancient world, for its corn, dates, balsam, flax, and other products” (Smith 487).

The Jordan Valley was the lifeblood of the Hebrew and Jewish people we encounter in the Christian Bible. Israelite culture developed in the Jordan Valley; it is an important and inseparable part of that culture.

The sixth and final distinct geographic feature we encounter as we continue to move east toward the desert is The Transjordan Plateau. The term “Beyond the Jordan” is more likely to be encountered in the Christian bible than the term “Transjordan” ( Gen. 50:10-11, Deut. 3:20, Matt. 4:15, et al.). This land overlooks the Jordan Valley lying to its west, and its drainage is a principal down-stream source for the Jordan River. Before the conquest the Transjordan was comprised of Bashan, Gilead, Ammon Moab, and Edom; after the conquest the region was occupied by the tribes of Reuben and Gad and the half-tribe of Manasseh (Nelson 1274), The Transjordan Plateau connects with the Syrian Desert to the northeast, Jordan to the east, and the Arabian Desert to the southeast ( Fig. 2).

The Palestinian climate is largely hot, and dry. The cooler, rainy season is from October to April, and is comprised of the "Former" Fall, and "Latter" Spring, rains, while the hot, dry season is from May to September ("Former" and "Latter" are an allusion to Joel 2:23 ). Importantly, there is no appreciable rainfall outside of the rainy season; severe, drought-like conditions prevail whenever the bi-annual rains are late or absent, thwarting agrarian subsistence. Presently annual rainfall is approximately 25 millimeters in the area of the Dead Sea; the Upper Galilee and the Coastal Plain regions average 108 millimeters annually ("Israel:Climate ").

The rich geographic diversity noted in section II directly relates to local temperature and humidity gradients very much a function of topography and location. Presently the Negev and Dead Sea locales experience average temperatures ranging from 21 degrees C in the winter, to 46 degrees C in the summer (extreme daily temperature swings are hidden in these averages). The coastal regions are mild, with average temperatures of 16 degrees C in the winter, and 29 degrees C in the summer. The mountains in Galilee are cooler, with some keeping snow on their peaks in the hotter season ("Israel:Climate").

One final climatic factor affecting Palestinian life is noteworthy. The dreaded East Winds, called Sirocco, which are a byproduct of the eastern desert, are a constant threat to agrarian Palestine. These winds can appear suddenly and literally scorch anything in their path (Gen. 41:6, Ezek. 17:10, et al.)

Palestinian culture during the time of our Savior's visitation was largely a peasant culture. The Jordan Valley was the home of small land owners, tenant farmers, and day laborers. Many of Jesus' parables addressed this peasant existence and multitudes, we are told, usually gathered to hear Him speak. It seems He was well appreciated by the so-called "everyday" people of the land (Am ha-aretz[4]), who must have been encouraged and gladdened by His message of hope, and witness of divine power. The people of His day were hardworking people, struggling to make a living and survive. By and large, the masses were poor, and at the mercy of their overlords' whims. Witness a small sampling of parables based on agrarian life, and our Savior's compassion for His people (Matt. 13:1-37, Matt. 20:1-16, Matt. 21:33-45, Matt. 14:14).

A prevalent language spoken in ancient (c. 1200-200 BC) Palestine was Biblical Hebrew. Near the beginning of the third-century BC, Hebrew was supplanted by the western dialect of Aramaic ("Hebrew Language"). In our Savior's day, Aramaic and Greek were the predominant languages of Palestine.

The conquests of Alexander the Great (336-323 BC) imposed upon Palestine an indelible influence of Greek culture. This culture was characterized by a fascination with pleasure, physical beauty, the human body, strength, the arts, music, philosophy, learning, multitudes of gods and goddesses, among other things. Greek culture of the day valued those things which offered the greatest pleasure in life, "here and now." It was very tolerant in its celebration of the human body, it was self-indulgent, and it was cosmopolitan. Greeks wanted to experience life at its fullest, in as many ways as possible, as often as possible. Clearly not all Greeks of the day fit this mold, but by and large this mold fit post-Alexander Greece in general. It was Alexander's desire to spread the Greek way of life throughout his empire as a means to internally unify and settle the same, specifically through the spread of the Greek language (his vehicle), which language embodied the culture. The Greek language was the expression of the ideas and thoughts that were sympathetic to the cultural characteristics just described. Hence, with the spread of the language inevitably came the spread of that culture. Alexander's experiment significantly accomplished its objective. Importantly, the Greek influence was imposed upon a Palestine that had tasted the culture of yet other conquering lands prior to Alexander. Dating to antiquity, the Egyptians, Hittites, Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians all exerted cultural influence upon Palestine (as did Rome subsequent to the Greeks), but none, it could be argued, had the degree of influence on Palestine as did the Greek invasion. It benefits us to appreciate Palestinian culture as it emerged in the time of Christ and shortly thereafter during the development of the early Christian Church, as a melting pot of many cultures—yet with distinct Hellenic overtones (Russell 21 ). The effect that Hellenism had on the Jewish people, particularly those contemporaries of our Lord Jesus, was profound and is discussed separately next.

We wish to turn our attention now specifically to those events which helped shape the Judaic mind-set that our Savior and His Apostles confronted.

After Alexander’s military exploits, and death in 323 BC, his empire was divided between the Seleucids (named after Seleucus I, general of Alexander's elite guard) in the north, centered in Syria, and the Ptolemies (named after Ptolemy I [Soter], general of Alexander's phalanx), in the south, centered in Egypt. In fact, Alexander's empire was split into four parts after his death, but these two dominant divisions concern us for this study. These successors to Alexander vied for control of Palestine in order to gain control of the Near East. Figure 1 illustrates the strategic location of Palestine directly between the two contenders. From 323-200 BC the Ptolemies dominated Palestine and imposed upon their subjects a tolerant, permissive rule, particularly in the area of religious freedom; Jews of that period were relatively free to worship according to ancestral tradition. In 200 BC the Ptolemies fell into a period of military weakness, and eventually the Seleucids gained domination of Palestine by their defeat of the Ptolemies at Paneas in northern Galilee in 198 BC. Under the pro-Greek Seleucid rule, Hellenization in Palestine changed colors. Hellenization is a term commonly associated with the civilization and culture that is a consequence of Alexander's military exploits and colonialism, namely, the Greek way of life. The term can largely be understood as follows: "to make Greek." Eager emigration of Greek nationals into the regions conquered by Alexander contributed in no small way to the Hellenization of the same (Roetzel 10 ). Under the Seleucids, Hellenization was imposed systematically within the empire. When an initially passive, tolerant means of Hellenization (Ptolemies) gave way to one of persecution, forced sacrilege, and temple defilement, particularly under the Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV (Epiphanes), Jewish Palestine revolted. The Maccabean revolt, begun in 167 BC by a Hasidim[5] priest named Mattathias of the house of Hasmon and effectively perpetuated by three of his sons and their followers (167-142 BC), gave Judaism victory over its enemies and their culture. Under the rule of these Hasidim brothers, usually referred to as the "Maccabees," and their five descendants, usually referred to as the "Hasmoneans," Jewish Palestine realized nearly eighty years of independence (142-63 BC). The apocryphal book of I Maccabees is widely accepted as providing an accurate history of the Maccabean struggle for independence.

Jews of the intertestamental period were largely scattered throughout Palestine. Importantly, with the exception of the relatively short period of Hasmonean-led independence, they were thrust into a culture diametrically opposite to that which for centuries embodied their spiritual roots and equilibrium; literally point-for-point, Greek culture and Jewish culture was diametrically opposite in nature (Table 1). The clash of these two cultures was ultimately the major drama of the intertestamental period—and it was played out on a Palestinian stage. The internal pressure of conformance, that is, the conservative-liberal Judaic split, particularly in the Seleucid era, between Hasidim-like Jews, and Hellenistic Jews (pro-Greek "modernizing" Jews), over the issue of conformance to the modern Greek world, and attendant abandonment of Judaic tradition, was perhaps the greatest struggle Jews dealt with during that time. Intertestamental Jews were under intense pressure from within, as just described, and without, due to location between two warring empires desiring to annex Palestine for selfish reasons. The intertestamental period was one of intense strain for Judaism. Table 2 summarizes the intertestamental period.

One can read through the Christian Bible and not appreciate that the events recorded there occurred in a very small space. Besides the presentation of the diverse topography of the land, the geography we presented was largely intended to bear out that small size. Our third incentive was to suggest that perhaps our God entered human history in Palestine because of its strategic lay.[6] By today’s estimates the three continents that Palestine bridges account for the vast majority of the human population (“World Population”), and it is very likely that was the case in Jesus’ day, and importantly, after the first century when the Christian Church began its outreach. There simply could not be a more efficient place from which to start an outreach than Palestine. This is especially true seeing that the Gospel spread throughout one of those continents—Europe—effecting conversion unto the one true God, Jehovah (=I AM—Exod. 3:13-14), until it was technologically feasible to carry it to the rest of the world and so effect conversion there (is it coincidental that Europe would be the center of that technological advance, as also the “proving ground” for the Gospel of Jesus Christ; or that parts of Asia and much of South Africa are today perhaps the most vibrant segment of Christianity?). It staggers the mind to realize that today Christianity is the world’s largest religion with over two-billion professing Christians—roughly one-quarter to one-third of the world’s population—and it all started from that little red strip in figure 1 (“Christianity”).

The climate of the land lends itself well to largely three professional activities—farming, fishing, and pastoralism. Over the centuries the daily grind attending these activities prepared a people for a ministry steeped in the language of these activities. Words like fruit, harvest, seed, sow, weed, cast, catch, fish, fisherman, net, feed, sheep, shepherd, staff, swine, etc., easily translated into parables by which our Savior could teach both the minister and the ministered—for at the outset both the minister and the ministered were the people of this land.

After the Hasmonean-led independence of the intertestamental period the scepter departed from Judah—the time was ripe for Shiloh to come (Gen. 49:10). But the time was not quite fulfilled for the appearing of His ministry, for it was necessary that a universal language, roads, mail systems, open shipping lanes, and so forth, be in place, and for the most part the Greek and early Roman periods provided these. Alexander’s spread of the Greek language was important in that the New Testament was written in that language[7]—when the Gospel went forth, it did so in a language Jew and Gentile alike understood. The Romans were master builders and organizers and largely provided the commercial and communicative infrastructure upon which the Gospel was carried[8].

When the time was fulfilled (Mark 1:14-15) our Savior’s ministry began (approximately from AD 30 to AD 33 or 34). He ministered in a time when Palestine was a procuratorship of Rome. The first procuratorship lasted from AD 6 to AD 41; this was a period of persecution and national unrest characterized by the hope for deliverance from the yoke of Rome—in the spirit of the triumphant Maccabean Revolt of the intertestamental period. Tough messianic pretenders (would-be kings of the Jews), in the spirit of the Maccabees, had shortly before our Lord’s ministry led rebellions to do just that (one Judas in Galilee [Antiquities 17.271-72=17.10.5], a certain Simon in Perea [Antiquities 17.273-76=17.10.6], and one called Athronges in Judea [Antiquities 17.278-85=17.10.7-8])—though unsuccessful, they were quite costly to Rome (in manpower, material, and prestige), and so put the Roman Eagle resolutely on its guard against even the hint of a messianic movement. It was into this kind of a volatile atmosphere that our Christ (=Greek Christos, tantamount to “messiah”) launched His ministry.[9]

When Caiaphas[10] asked our Lord the loaded question (i.e., double-edged, as in consisting of a treason component and a blasphemy component) —SU EI hO CRISTOS hO UIOS TOU EULOGHTOU? ...Jesus’ response—EGW EIMI… (= question—Are you the Christ [=messiah—the treason component], the son of the blessed One? [the blasphemy component] Jesus’ response—I am…Mark 14:61-62), he asked it both to entrap our Lord, and to justify his ulterior motives in the minds of the Jews. Caiaphas knew quite well that a charge of blasphemy would not hold sway with Rome—who alone could execute our Lord (the Jews did not have the authority to do so). It was the Jews he sought to appease with the blasphemy component (Mark 14:64); his real goal was to entrap our Lord so as to obtain some evidence of treason against Him, and so present Him as an insurrectionist/messianic pretender to Rome, whom he knew would then summarily execute Him. Jesus’ emphatic answer in the affirmative (EGW EIMI… =I am, with further self-identification as the Son of Man seated at the right hand of the power on high) was His own death sentence. “I am” was the only answer possible for our Lord, of course. Jesus’ crown of thorns (Mark 15:17) and the placard over His cross: “The King of the Jews” (Mark 15:26) are symbolic of the charge against Him: treason—a perceived threat to Roman sovereignty in first-century AD Palestine.

Praised be your name King Jesus.

|

ASPECT |

JUDAIC CULTURE |

GREEK CULTURE |

|

- |

Shadow of Christianity |

Shadow of antiChristianity |

|

AIM |

Eternal Bliss |

Temporal Bliss |

|

PERSPECTIVE |

Provincial |

Cosmopolitan |

|

ORIENTATION |

Spiritual |

Secular |

|

GOVERNMENT |

Theocratic |

Despotic, Democratic |

|

LAW |

Mosaic |

Civil |

|

THEISIM |

Monotheistic |

Polytheistic |

______________________________

450-400 BC-approximate date of the writing of Malachi, last canonical book of the Old Testament.

336-323 BC-military conquests-death of Alexander the Great.

323-301 BC-Alexander's generals, satraps, contend for control of his empire.

301 BC-battle of Ipsus in Phrygia (modern-day central Turkey) establishes general-Ptolemy I (Soter) in Egypt, and all of Palestine south of Damascus; establishes general-Seleucus I in northern Syria and eastward, through former Babylonian empire, up to nearly India.

284-246 BC-Ptolemy II (Philadelphus) continues resettlement of Jews to Alexandria begun by Ptolemy I (Soter), expands Alexandrian library founded by Ptolemy I (Soter); Hebrew Scriptures translated into Greek giving rise to the Septuagint; Judaic tension over issue of conformance to Greek culture; emergence of Hasidim and Hellenizing Jews.

200-198 BC-Ptolemies fall into period of military weakness.

198 BC-Antiochus III, Seleucids, gain control of all of Palestine by defeat of Ptolemies at Paneus, in northern Galilee (i.e., Caesarea Philippi, near Mount Hermon); Antiochus III promises Palestinian subjects continuation of Ptolemaic policy of benign, tolerant Hellenization but pro-Greek policy manifested instead.

198-170 BC-Rome encroaches on Seleucid empire in west, shrinks Seleucid tax base; Seleucus IV (Philopator), successor to Antiochus III, assassinated; Antiochus IV (Epiphanes) succeeds Seleucus IV (Philopator); Jason, brother of ancestrally legitimate Jewish High Priest Onias III buys High Priesthood from Antiochus IV (Epiphanes), Onias III deposed; Jason builds gymnasium next to temple in Jerusalem; ancestrally illegitimate Jew Menelaus out-bids Jason and appointed Jewish High Priest by Antiochus IV (Epiphanes), Jason deposed, Onias III killed, unprecedented abuse of High Priesthood; Antiochus IV (Epiphanes) frustrated in Egypt by resurgent Ptolemies; Jason snatches High Priesthood from Menelaus; Sabbath-day assault on Jerusalem by Antiochus IV (Epiphanes), slaughters thousands, erects Seleucid garrison near temple; Seleucid Hellenizing policy turns from tolerance to persecution and sacrilege.

167 BC-Antiochus IV (Epiphanes) desecrates Jewish temple by sacrificing a sow to the Olympian god Zeus on Jehovah's Altar of Burnt Offerings; Jews ordered to renounce their faith (i.e., religious practices counter to pagan worship) under threat of death.

167-142-BC Maccabean revolt, Jewish Independence struggle, led by Hasidim priest Mattathias the Hasmonean, successfully effected by sons Judas, Jonathan, Simon, and Hasidim freedom-fighters; reclaim Jerusalem, re-consecrate temple (Hanukkah), expand Jewish territory to include Coastal Plain, Central Highlands, Trans-Jordan Plateau; Jonathon appointed High Priest; independence granted; Hasidim governance in Judah.

142-63 BC-Hasmonean Dynasty--the era of priest-kings; Simon appointed hereditary High Priest and ethnarch; accession of John Hyrcanus I, governance rotates to Hellenizers; emergence of Pharisees, Sadducees; San Hedrin likely established;

63-4 BC-Pompey seizes Palestine, independence lost, onset of the Roman period, Judah becomes part of the Roman province of Syria; Rome continues policy of Hellenization initiated by former rulers of Palestine; Rome levies burdensome taxes, kindles memory of Maccabean independence struggle; accession and death of Herod the Great; virgin birth of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.

AD 30-33-ministry of Jesus Christ.

AD 33-65-oral transmission of Gospels; ministry of Paul.

AD 66-70-taxation-induced Jewish-Roman war; destruction of Jerusalem by Titus.

First-century AD-writing of the books of the New Testament; beginning of the outreach of the Christian Church.

Table 2 Sources:

[a] LaHaye 992

[b] Niswonger 19-39

[c] Roetzel 9-23

[d] Russell 13-40

Wikipedia

< http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christianity>

"East African Rift System/Great Rift Valley."

Wikipedia.

< http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Rift_Valley >

Wikipedia.

< http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hebrew_language >

Horsley, Richard A. with John S. Hanson.

Bandits Prophets & Messiahs.

Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1999.

Wikipedia.

< http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Climate_of_Israel#Climate >

Wikipedia.

< http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jezreel_Valley >

Wikipedia.

< http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jordan_River >

LaHaye, Tim, Edward Hindson, ed.

Tim LaHaye Prophecy Study Bible .

AMG Publishers, 2000. 0-89957-932-9.

New Testament History.

Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1992. 0-310-312019.

Melton, Lloyd. Professor of New Testament,

Trinity Theological Seminary, Newburgh, Indiana;

New Testament History, Cassette 1.

Nelson’s Illustrated Bible Dictionary.

Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1995.

Wikipedia.

< http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palestine>

Wikipedia.

< http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philistines >

The World That Shaped The New Testament .

Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1985. 0-8042-0455-1.

Between the Testaments.

Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1968. 0-8006-1856-4.

Wikipedia..

< http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plain_of_Sharon >

The Historical Geography of the Holy Land.

Armstrong and Son, 1903.

Wikipedia.

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_population>

[1] By intertestamental we mean roughly that period between the reestablishment of the Jews in Jerusalem after the Babylonian Captivity, and the birth of Jesus Christ—the term is meant to signify the period between the last events of the Old Testament and the beginning of the events of the New Testament—which is the birth of our Lord Jesus on the latter end, and the end of the Persian Period on the former end. Our Table 2 conveniently uses the proposed date of the writing of the last book of the Old Testament and the birth of Christ here.

[2] Holy Bible New Living Translation-map: Israel and the Middle East Today, p. 1470.

[3] Idea suggested by Dr. Lloyd Melton, Trinity Theological Seminary, Newburgh, Indiana

[4] Am ha-aretz is a Hebrew construct chain that means people of the land.

[5] Hasidim is Hebrew for "Pious Ones;" they were an unorganized puritan sect of pious Jews, forerunners of the Pharisees and Essenes.

[6] Knowing that He would minister in Palestine, He chose a people through which to foreshadow Himself and His requirements—but the choice of a specific land perhaps He would have made first.

[7] The common man’s Greek or Koine Greek.

[8] The Romans built upon works laid down by the Persians.

[9] It is an observable feature of the Creation that for every effect there is a cause. This axiom extends to the messianic movements here discussed. These movements sprang up in consequence to oppression—civil, national, and/or spiritual oppression (Horsley, passim). Like a bow stretched taut, the pent up anger and frustration of the oppressed, replete with extensive pain and suffering, became a weapon of political opportunity and/or bloody retribution in the hands of mundane messiahs long on brawn and charisma, resolve and even, to some degree, merit, but all terribly short on efficacious novelty. That is, ineffective insofar as their movements did not break the cycle of oppression nor novel insofar as their tactics fostered yet more oppression—the kind that attends the old familiar tactics of violence and bloodshed. This of course only served to quicken the hope for a Messianic Kingdom, the ideal of which lay beyond the reach of mundane messianism. Indeed, the ideal of the Messianic Kingdom is the Kingdom of Heaven itself, and all that it embodies (Mark 1:14-15).

[10] Matthew and John identify Caiaphas here—.Matt. 26:57ff, John 18:24, our source and Luke refer to him by title only.